Triangulation

Problem definition

Given camera matrices (\(P, P'\)), or fundamental matrix \(F\), and measured image points \(x\) and \(x'\), estimate the 3D point \(X\) that minimizes some cost function.

Since the rays back-projected from the points are skew. There will not be a point \(X\) that satisfies \(x=PX, x'=P'X\), the the image points do not satisfy the epipolar constraint \(x'^\top F x= 0\).

Since from a fundamental matrix and a set of corresponding points, the scene can only be reconstructed up to a projective transformation. Thus, it is crucial to have a triangulation method that is invariant to projective transformation.

Denote \(\tau\) as the triangulation method used to compute a 3D point \(X\) from a point correspondence \(x\leftrightarrow x'\) and a pair of camera matrices \(P, P'\). We have

\[X = \tau(x, x', P, P')\]The invariance to projective transformation \(H\) is expressed as

\[\tau(x, x', P, P') = H^{-1}\tau(x, x', PH^{-1}, P'H^{-1})\]Results

I implemented three different triangulation method, a linear, a midpoint, and a nonlinear triangulation. The test code and results are as follows

int main(const int argc, const char** argv)

{

int npts = 2;

vector<Mat34f> poses(npts);

Mat3f K, R;

Vec3f t;

K << 1520.400000, 0.000000, 302.320000,

0.000000, 1525.900000, 246.870000,

0.000000, 0.000000, 1.000000;

R << 0.02187598221295043000, 0.98329680886213122000, -0.18068986436368856000,

0.99856708067455469000, -0.01266114646423925600, 0.05199500709979997700,

0.04883878372068499500, -0.18156839221560722000, -0.98216479887691122000;

t << -0.0726637729648, 0.0223360353405, 0.614604845959;

poses[0].block<3, 3>(0, 0) = K * R;

poses[0].block<3, 1>(0, 3) = K * t;

K << 1520.400000, 0.000000, 302.320000,

0.000000, 1525.900000, 246.870000,

0.000000, 0.000000, 1.000000;

R << -0.03472199972816788400, 0.98429285136236500000, -0.17309524976677537000,

0.93942192751145170000, -0.02695166652093134900, -0.34170169707277304000,

-0.34099974317519038000, -0.17447403941185566000, -0.92373047190496216000;

t << -0.0746307029819, 0.0338148092011, 0.600850565131;

poses[1].block<3, 3>(0, 0) = K * R;

poses[1].block<3, 1>(0, 3) = K * t;

Vec2f xrange(-0.073568, 0.028855), yrange(0.021728, 0.181892), zrange(-0.012445, 0.062736);

srand (time(NULL));

vector<float> err(3);

err[0] = err[1] = err[2] = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < 100; ++i)

{

float a = float(rand()) / RAND_MAX;

Vec3f X;

X << a * (xrange(1) - xrange(0)) + xrange(0),

a * (yrange(1) - yrange(0)) + yrange(0),

a * (zrange(1) - zrange(0)) + zrange(0);

vector<Vec3f> centers(npts);

vector<Vec3f> directs(npts);

vector<Vec2f> pts(npts);

for (int i = 0; i < npts; ++i)

{

Vec3f x = poses[i] * X.homogeneous();

pts[i] = x.block<2, 1>(0, 0) / x(2);

Mat4f M;

M.block<3, 4>(0, 0) = poses[i];

M.block<1, 4>(3, 0).setZero();

Vec4f c;

nullspace<Mat4f, Vec4f>(&M, &c);

centers[i] = c.block<3, 1>(0, 0) / c(3);

directs[i] = poses[i].block<1, 3>(2, 0);

directs[i] /= directs[i].norm();

}

Vec3f X_est;

// linear triangulation

triangulate_linear(poses, pts, X_est);

err[0] += (X - X_est).dot(X - X_est);

// midpoint triangulation

triangulate_midpoint(centers, directs, pts, X_est);

err[1] += (X - X_est).dot(X - X_est);

// nonlinear triangulation

triangulate_nonlinear(poses, pts, X_est);

err[2] += (X - X_est).dot(X - X_est);

}

cout << "linear triangulation: " << err[0] / 100 << endl;

cout << "midpoint triangulation: " << err[1] / 100 << endl;

cout << "nonlinear triangulation: " << err[2] / 100 << endl;

}

Here is a typical result of one execution. We can see the nonlinear triangulation gives the best, whereas the midpoint triangulation gives the worst result.

linear triangulation: 2.95963e-15

midpoint triangulation: 0.00366608

nonlinear triangulation: 9.65e-16

Linear triangulation

We first discuss a simple linear triangulation method, which is similar to the DLT method for homography estimation.

By definition, we have \(x = PX, x'=P'X\). We can get rid of the homogeneous scale factory by a cross product. Therefore, \(x\times PX=0\). This can be rewritten as

\[\begin{align} x(\mathbf{p^{3\top}}\mathbf{X})-(\mathbf{p^{1\top}}\mathbf{X}) &=0\\ y(\mathbf{p^{3\top}}\mathbf{X})-(\mathbf{p^{2\top}}\mathbf{X}) &=0\\ x(\mathbf{p^{2\top}}\mathbf{X})-y(\mathbf{p^{1\top}}\mathbf{X}) &=0\\ \end{align}\]where \(\mathbf{p^{i\top}}\) is the \(i\)th row of \(P\). Only two of these equations are linear independent.

An equation of the form \(A\mathbf{X} = 0\) can be formed from the image points, with

\[A= \begin{bmatrix} x(\mathbf{p^{3\top}})-(\mathbf{p^{1\top}})\\ y(\mathbf{p^{3\top}})-(\mathbf{p^{2\top}})\\ x'(\mathbf{p^{3\top}})-(\mathbf{p^{1\top}})\\ y'(\mathbf{p^{3\top}})-(\mathbf{p^{2\top}})\\ \end{bmatrix}\]There are typically two ways of solving this problem:

Homogeneous method (DLT)

The solution is the unit singular vector corresponding to the smallest singular value of \(A\).

Inhomogeneous method

Set \(\mathbf{X} = [X, Y, Z, 1]\), \(A\mathbf{X}=0\) can be converted to a set of four inhomogeneous equations with three unknowns. This technique fails to work when the last coordinate of \(\mathbf{X}\) is close to 0.

NOT projective invariant

Unfortunately, this linear method is NOT projective invariant. Let’s consider another camera matrix pair: \(PH^{-1}, P'H^{-1}\). The matrix A, in this case, becomes \(AH^{-1}\). It’s easy to verify that the 3D point \(X\) that satisfies \(A\mathbf{X}=\epsilon\) also satisfies the new linear system \((AH^{-1})(H\mathbf{X})=\epsilon\). Thus, there is a one-to-one correspondence between point \(X\) and \(HX\) that gives the same error. However, the constraints for both the homogeneous method (\(\|X\|=1\)) and inhomogeneous method (\(\mathbf{X}=[X,Y,Z,1]^\top\)) are not invariant under projective transformation. Thus, in general the point \(\mathbf{X}\) solving the original problem will not correspond to a solution \(H\mathbf{X}\) for the transformed problem. However, there is a special case: for affine reconstruction, the inhomogeneous method is affine transformation invariant. Please refer to the MVG book by Hartley and Zisserman for details.

Here is a the C++ version of the linear triangulation solved by the homogeneous method. The Matlab version is in the VGG toolbox, which is named vgg_X_from_xP_lin.

void triangulate_linear(const vector<Mat34f>& poses, const vector<Vec2f>& pts, Vec3f& pt_triangulated)

{

Matf A(2 * pts.size(), 4);

for (int i = 0; i < pts.size(); ++i)

{

float x = pts[i](0);

float y = pts[i](1);

const Mat34f pose = poses[i];

Vec4f p1t = pose.row(0);

Vec4f p2t = pose.row(1);

Vec4f p3t = pose.row(2);

Vec4f a = x * p3t - p1t;

Vec4f b = y * p3t - p2t;

a.normalize();

b.normalize();

A.block<1, 4>(2 * i, 0) = a.transpose();

A.block<1, 4>(2 * i + 1, 0) = b.transpose();

}

Vec4f X;

nullspace<Matf, Vec4f>(&A, &X);

pt_triangulated = X.block<3, 1>(0, 0).array() / X(3);

}

Midpoint triangulation

This method computes the 3D scene structure using midpoint triangulation. Richard I. Hartley and Peter Sturm mentioned in their paper “Triangulation” that this method is neither affine nor projective invariant, since concepts such as perpendicular or mid-point are not affine concepts. It is seen to behave very poorly indeed under projective and affine transformation, and is by far the worst of the methods considered here in this regard. We include this for the sake of completeness.

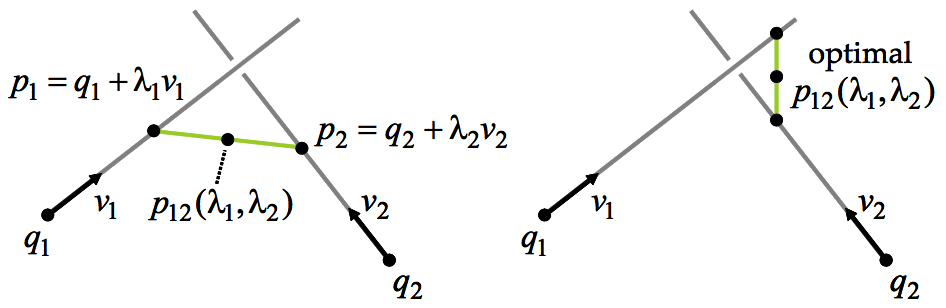

Here we consider the case of two arbitrary lines \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) \[L_1=\{p=q_1+\lambda_1v_1|\lambda_1\in\mathbb{R}\}\] \[L_2=\{p=q_2+\lambda_2v_2|\lambda_2\in\mathbb{R}\}\]

If vectors \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are linearly dependent, i.e., one is the scalar multiple of the other. In addition, suppose \(q_2 - q_1\) is also the multiple of \(v_1\) or \(v_2\), then these two lines are essentially a single line. Otherwise, these two lines are parallel and do not intersect.

If vector \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are linearly independent, these two lines may or may not intersect. the sufficient and necessary condition for two lines to intersect is that scalar values \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) exist so that

\[q_1 + \lambda_1v_1=q_2+\lambda_2v_2\]

If two lines do not intersect, we find the approximate intersection as the point that is closest to the two lines. More specifically, we define the approximate intersection as the point \(p\) which minimizes the sum of the square distances to both lines

\[\phi(p, \lambda_1, \lambda_2)=\|q_1+\lambda_1 v_1-p\|^2 + \|q_2+\lambda_2 v_2-p\|^2\]

The function \(\phi(p, \lambda_1, \lambda_2)\) is a quadratic non-negative definite function of five variables, the three coordinates of the point \(p\) and the two scalars \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\). Let \(p_1 = q_1 + \lambda_1 v_1\) be a point on the line \(L_1\), and \(p_2 = q_2 + \lambda_2 v_2\) be a point on the line \(L_2\). A necessary condition for the minimizer \((p, \lambda_1, \lambda2)\) is that the partial derivative of \(\phi\), with respect to the five variables, all vanish at the minimizer. In particular, the derivatives w.r.t. the three coordinates of the point \(p\) must vanish

\[\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial p} = (p-p_1)+(p-p_2)=0\]

or equivalently, it is necessary for the minimizer point \(p\) to be the midpoint of the line segment joining \(p_1\) and \(p_2\).

As a result, the problem reduces to the minimization of the squared distance from a point \(p_1\) on line \(L_1\) to a point \(p_2\) on line \(L_2\). The original cost function becomes a quadratic non-negative definite function of two variables

\[\psi(\lambda_1, \lambda_2)= 2\phi(p, \lambda_1, \lambda_2) = \|(q_2+\lambda_2 v_2) - (q_1 + \lambda_1 v_1)\|^2\]

It is necessary for the partial derivatives of \(\psi\), w.r.t. \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) to be equal to zeros at the minimum, as follows

\[\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial \lambda_1} = v_1^\top (\lambda_1v_1-\lambda_2v_2+q_1-q_2) = \lambda_1\|v_1\|^2 - \lambda_2v_1^\top v_2+v_1^\top (q_1-q_2) = 0\] \[\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial \lambda_2} = v_2^\top (\lambda_2v_2-\lambda_1v_1+q_2-q_1) = \lambda_2\|v_2\|^2 - \lambda_2v_2^\top v_1+v_2^\top (q_2-q_1) = 0\]

These provide two linear equations in \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\), which can be expressed in the matrix form as

\[\begin{bmatrix} \|v_1\|^2 & -v_1^\top v_2\\ -v_2^\top v_1 & \|v_2\|^2\\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \lambda_1 \\ \lambda_2 \\ \end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix} v_1^\top (q_2-q_1)\\ v_2^\top (q_1-q_2) \end{bmatrix}\]Or equivalently

\[\begin{bmatrix} \lambda_1 \\ \lambda_2 \\ \end{bmatrix}= \frac{1}{\|v_1\|^2\|v_2\|^2-(v_1^\top v_2)^2} \begin{bmatrix} \|v_1\|^2 & v_1^\top v_2\\ v_2^\top v_1 & \|v_2\|^2\\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} v_1^\top (q_2-q_1)\\ v_2^\top (q_1-q_2) \end{bmatrix}\]Here is the C++ implementation of the midpoint triangulation

void triangulate_midpoint(const vector<Vec3f>& centers, const vector<Vec3f>& directions, const vector<Vec2f>& pts, Vec3f& pt_triangulated)

{

double min_dist = numeric_limits<float>::max();

Vec3f min_midpoint(0, 0, 0);

int size_pts = static_cast<int>(pts.size());

for (int i = 0; i < size_pts; ++i)

{

Vec3f center1 = centers[i];

Vec3f direct1 = directions[i];

for (int j = i + 1; j < size_pts; ++j)

{

Vec3f center2 = centers[j];

Vec3f direct2 = directions[j];

Vec3f direct_cross = direct1.cross(direct2);

float denom = 1.0f / direct_cross.dot(direct_cross);

float a1 = ((center2 - center1).cross(direct2)).dot(direct_cross) * denom;

float a2 = ((center2 - center1).cross(direct1)).dot(direct_cross) * denom;

Vec3f p1 = center1 + a1 * direct1;

Vec3f p2 = center2 + a2 * direct2;

Vec3f d = p1 - p2;

float dist = sqrt(d.dot(d));

Vec3f cd = center1 - center2;

float cdist = sqrt(cd.dot(cd));

Vec3f midpoint = (p1 + p2) * 0.5;

min_midpoint = dist * cdist < min_dist ? (min_dist = dist * cdist), midpoint : min_midpoint;

if (dist * cdist < 0.1f)

{

pt_triangulated = min_midpoint;

}

}

}

pt_triangulated = min_midpoint;

}

Geometric triangulation

Let \(x\leftrightarrow x'\) be the measured point correspondence, and \(\hat{x}\leftrightarrow \hat{x'}\) be the estimated point correspondence that satisfy the epipolar constraint, i.e., \(\hat{x'}^\top F \hat{x}=0\). This method minimizes the geometric distance between the measured and estimated points

\[C(x, x')=d(x, \hat{x}) + d(x', \hat{x'})\]Sampson approximation

Here is a the C++ version of the nonlinear triangulation. The Matlab version is in the VGG toolbox, which is named vgg_X_from_xP_nonlin.

void triangulate_nonlinear(const vector<Mat34f>& poses, const vector<Vec2f>& pts, Vec3f& pt_triangulated)

{

int sz = static_cast<int>(pts.size());

triangulate_linear(poses, pts, pt_triangulated);

Mat4f T, Ttmp;

Eigen::Matrix<float, 1, 4> pt_triangulated_homo = pt_triangulated.transpose().homogeneous();

Mat4f A;

A.setZero();

A.block<1, 4>(0, 0) = pt_triangulated_homo;

Eigen::JacobiSVD<Mat4f> asvd(A, Eigen::ComputeFullV);

T = asvd.matrixV();

// svd<Eigen::Matrix<float, 1, 4>, Mat4f, Mat4f>(&pt_triangulated_homo, nullptr, nullptr, &T);

Ttmp.block<4, 3>(0, 0) = T.block<4, 3>(0, 1);

Ttmp.block<4, 1>(0, 3) = T.block<4, 1>(0, 0);

T = Ttmp;

vector<Mat34f> Q(sz);

for (int i = 0; i < sz; ++i)

{

Q[i] = poses[i] * T;

}

// Newton

Vec3f Y(0, 0, 0);

Vecf err_prev(2 * sz), err(2 * sz);

Matf J(2 * sz, 3);

err_prev.setOnes();

err_prev *= numeric_limits<float>::max();

const int niters = 10;

for (int i = 0; i < niters; ++i)

{

residule(Y, pts, Q, err, J);

if (1 - err.norm() / err_prev.norm() < 10e-8)

break;

err_prev = err;

Y = Y - (J.transpose() * J).inverse() * (J.transpose() * err);

}

Vec4f X = T * Y.homogeneous();

pt_triangulated = X.block<3, 1>(0, 0).array() / X(3);

}

void residule(const Vec3f& pt3d, const vector<Vec2f>& pts, const vector<Mat34f>& Q, Vecf& e, Matf& J)

{

int sz = static_cast<int>(pts.size());

Vec3f x;

for (int i = 0; i < sz; ++i)

{

Mat3f q = Q[i].block<3, 3>(0, 0);

Vec3f x0 = Q[i].block<3, 1>(0, 3);

x = q * pt3d + x0;

e.block<2, 1>(2 * i, 0) = x.block<2, 1>(0, 0) / x(2) - pts[i];

J.block<1, 3>(2 * i, 0) = (x(2) * q.row(0) - x(0) * q.row(2)) / powf(x(2), 2.0);

J.block<1, 3>(2 * i + 1, 0) = (x(2) * q.row(1) - x(1) * q.row(2)) / powf(x(2), 2.0);

}

}

Optimal triangulation (non-iterative)

Let \(x\leftrightarrow x'\) be the measured point correspondence, and the goal of geometric error proposed above is to find a pair of estimated points \(\hat{x}\leftrightarrow \hat{x'}\) that minimize the SSD subject to the epipolar constraint \(\hat{x'}^\top F \hat{x}=0\). However, this formulation requires iterative techniques to solve the problem. This cost function can be reformulated so that a non-iterative algorithm can be used.

Since the estimated points lie on the epipolar lines, more specifically, \(\hat{x}\) lies on line \(l\) while \(\hat{\mathbf{x'}}\) lies on line \(\mathbf{l'}\). Minimize the distance \(d(x, \hat{x})\), where \(\hat{x}\in l\) is the same as minimizing the distance from the point \(x\) to the line \(l\), therefore, the cost function can be rewritten as

\[d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{l})+d(\mathbf{x'}, \mathbf{l'})\][TBD]

Angular triangulation

Computes the 3D scene structure using the algorithm proposed in WACV ‘12 by Recker et. al. This implementation uses a midpoint start and also uses an adaptive gradient descent for optimization.

StructurePoint Triangulation::angular(const vector<Camera> &cameras,

const FeatureTrack &track) const

{

double precision = 1e-25;

StructurePoint point = midpoint(cameras, track);

Vector3d g_old;

Vector3d x_old;

Vector3d x_new = point.coords();

Vector3d grad = angular_gradient(cameras, track, x_new);

double epsilon = .001;

double diff;

int count = 150;

do {

x_old = x_new;

g_old = grad;

x_new = x_old - epsilon * g_old;

grad = angular_gradient(cameras, track, x_new);

Vector3d sk = x_new - x_old;

Vector3d yk = grad - g_old;

double skx = sk.x();

double sky = sk.y();

double skz = sk.z();

diff = skx*skx+sky*sky+skz*skz;

//Compute adaptive step size (sometimes get a divide by zero hence

//the subsequent check)

epsilon = diff/(skx*yk.x()+sky*yk.y()+skz*yk.z());

epsilon = (epsilon != epsilon) ||

(epsilon == numeric_limits<double>::infinity()) ? .001 : epsilon;

--count;

} while(diff > precision && count-- > 0);

if(isnan(x_new.x()) || isnan(x_new.y()) || isnan(x_new.z())) {

return point;

}

return StructurePoint(x_new, point.color());

}

Vector3d Triangulation::angular_gradient(const vector<Camera> &cameras,

const FeatureTrack &track, const Vector3d &point) const

{

Vector3d g = Vector3d(0,0,0);

for(unsigned int i = 0; i < track.size(); ++i) {

const Keypoint& f = track[i];

const Camera& cam = cameras[f.index()];

Vector3d w = cam.direction(f.coords());

Vector3d v = point - cam.position();

double denom2 = v.dot(v);

double denom = sqrt(denom2);

double denom15 = pow(denom2, 1.5);

double vdotw = v.dot(w);

g.x() += (-w.x()/denom) + ((v.x()*vdotw)/denom15);

g.y() += (-w.y()/denom) + ((v.y()*vdotw)/denom15);

g.z() += (-w.z()/denom) + ((v.z()*vdotw)/denom15);

}

return g;

}